COVER STORY

September 2025

Cyberattacks Are Killing Hospitals. Here’s How to Survive.

Cyberattacks are no longer just a threat for hospitals, they’re an inevitability. The real question is whether or not your organization has the resilience to survive the financial, legal, and patient safety fallout.

COVER STORY

September 2025

Cyberattacks Are Killing Hospitals. Here’s How to Survive.

Cyberattacks are no longer just a threat for hospitals, they’re an inevitability. The real question is whether or not your organization has the resilience to survive the financial, legal, and patient safety fallout.

TAKEAWAYS

- Cyberattacks on hospitals are inevitable and escalating, with ransomware incidents more than doubling from 2016 to 2021 and healthcare facing the most cyberthreats of any critical infrastructure last year.

-

The focus has shifted from prevention to resilience, as leaders stress rapid recovery, patient safety, and continuity of care when systems go down.

- Smaller and rural hospitals face the greatest risks, lacking resources to respond, which experts warn could jeopardize communities unless targeted policy support and funding are provided.

TAKEAWAYS

- Cyberattacks on hospitals are inevitable and escalating, with ransomware incidents more than doubling from 2016 to 2021 and healthcare facing the most cyberthreats of any critical infrastructure last year.

-

The focus has shifted from prevention to resilience, as leaders stress rapid recovery, patient safety, and continuity of care when systems go down.

-

Smaller and rural hospitals face the greatest risks, lacking resources to respond, which experts warn could jeopardize communities unless targeted policy support and funding are provided.

If you’re a hospital or health system leader, chances are your organization has already been hit by a cyberattack, and more than once. The disturbing reality is that hospitals have become one of the most vulnerable targets in the nation’s critical infrastructure. And while executives once believed the goal was to keep attackers out, the industry now faces a far more controversial truth: prevention is no longer enough.

“An average health system of 10,000 users is being attacked an average of 200 times per second,” Saad Chaudhry, chief digital and information officer at SSM Health, says. “In this monologue that I just gave you, we’ve all been attacked tens of thousands of times already. So, absolutely incidents are going to happen.”

So, the defining question isn’t whether you can avoid a breach, it’s whether your hospital can survive one.

This uncomfortable shift has ignited fierce debate among healthcare leaders, policymakers, and technology experts. Should hospitals be expected to shoulder the escalating financial, legal, and patient safety risks alone? Or is it time for federal and state governments to intervene with dedicated funding, policy reform, and coordinated response systems?

At stake is not just cybersecurity, it’s the continuity of patient care and, in many communities, the survival of the hospital itself.

From Hardening the Shell to Recovering Fast

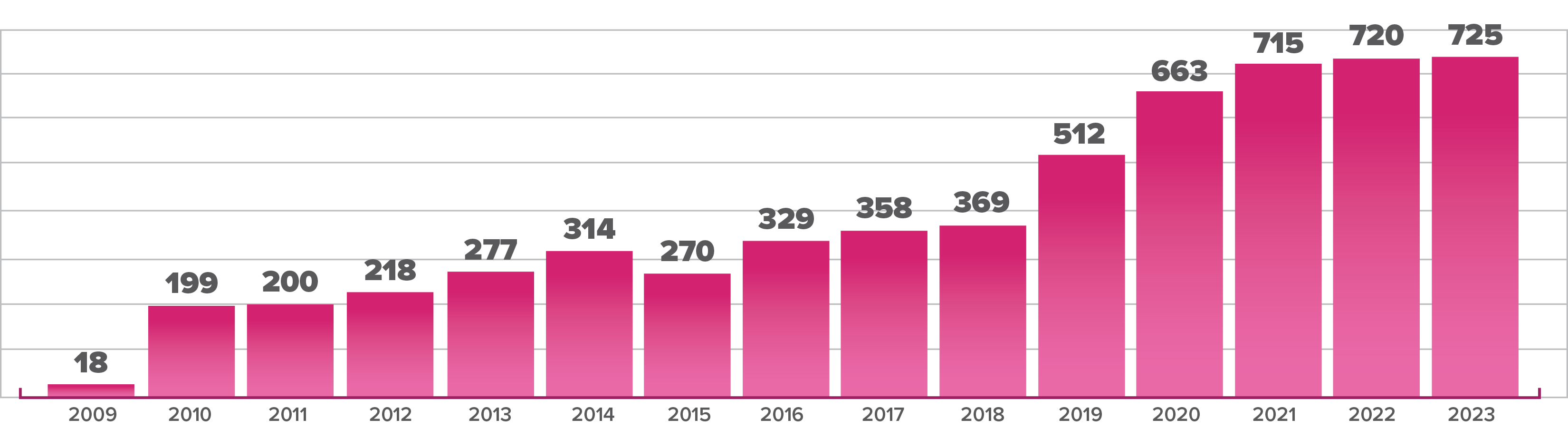

Over the past decade, cyberattacks on hospitals have increased exponentially. From 2016 to 2021 alone, the annual number of ransomware attacks on healthcare delivery organizations more than doubled, with hospitals most likely to experience a disruption due to an incident, according to a study published in JAMA Health Forum.

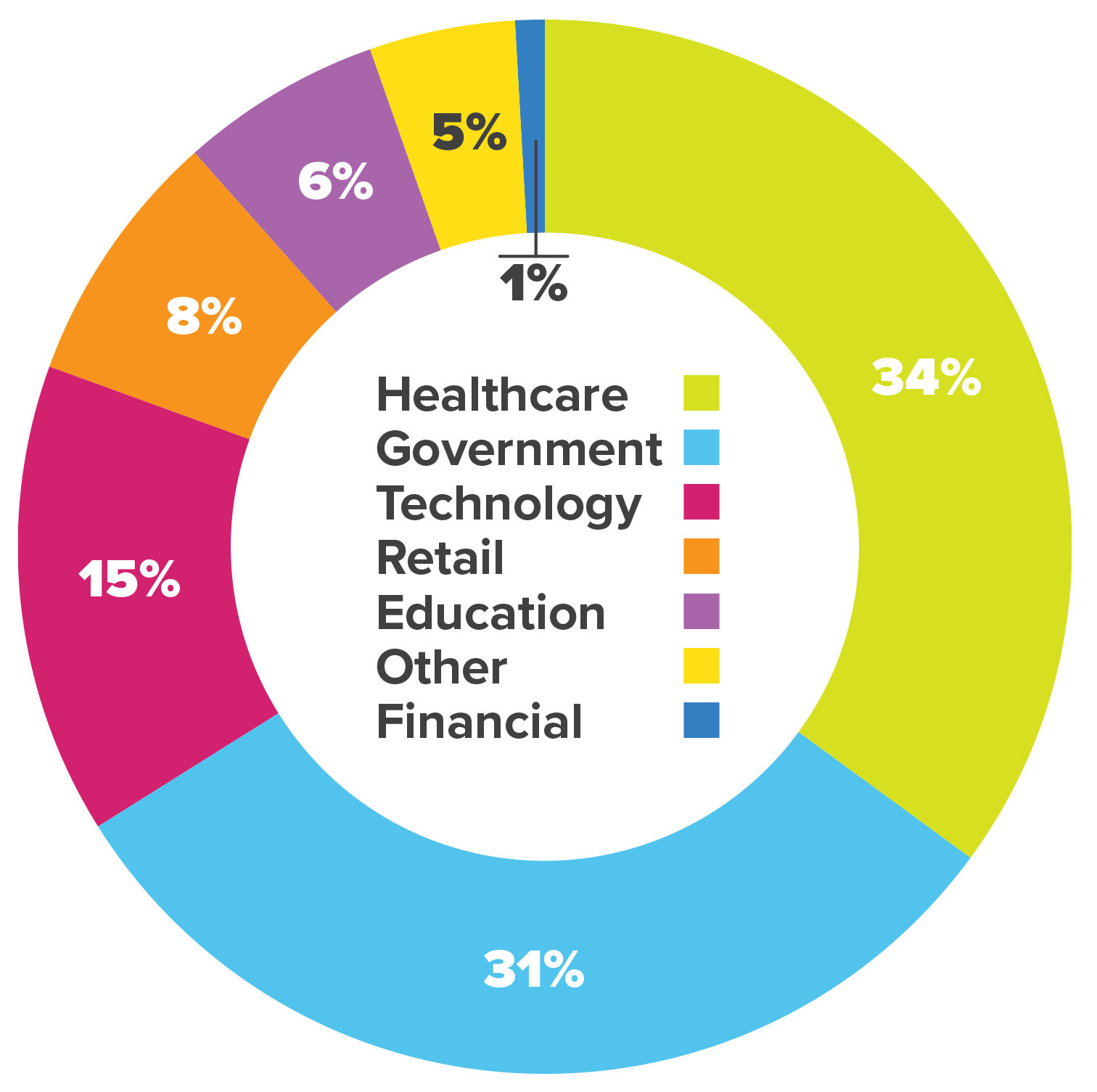

In 2024, healthcare had more cyberthreats than any other critical infrastructure industry, experiencing 238 ransomware threats and 206 data breaches, the FBI’s Internet Crime Report found.

The Change Healthcare cyberattack can be considered, in some ways, an inflection point for cybersecurity in the industry. When the subsidiary of UnitedHealth Group experienced a ransomware attack in February 2024, it exposed the data of millions of Americans and disrupted operations across Change Healthcare’s provider network.

It wasn’t a direct strike on hospitals and health systems, but it proved just how devastated those organizations can be when a data breach hampers their ability to submit and receive payments.

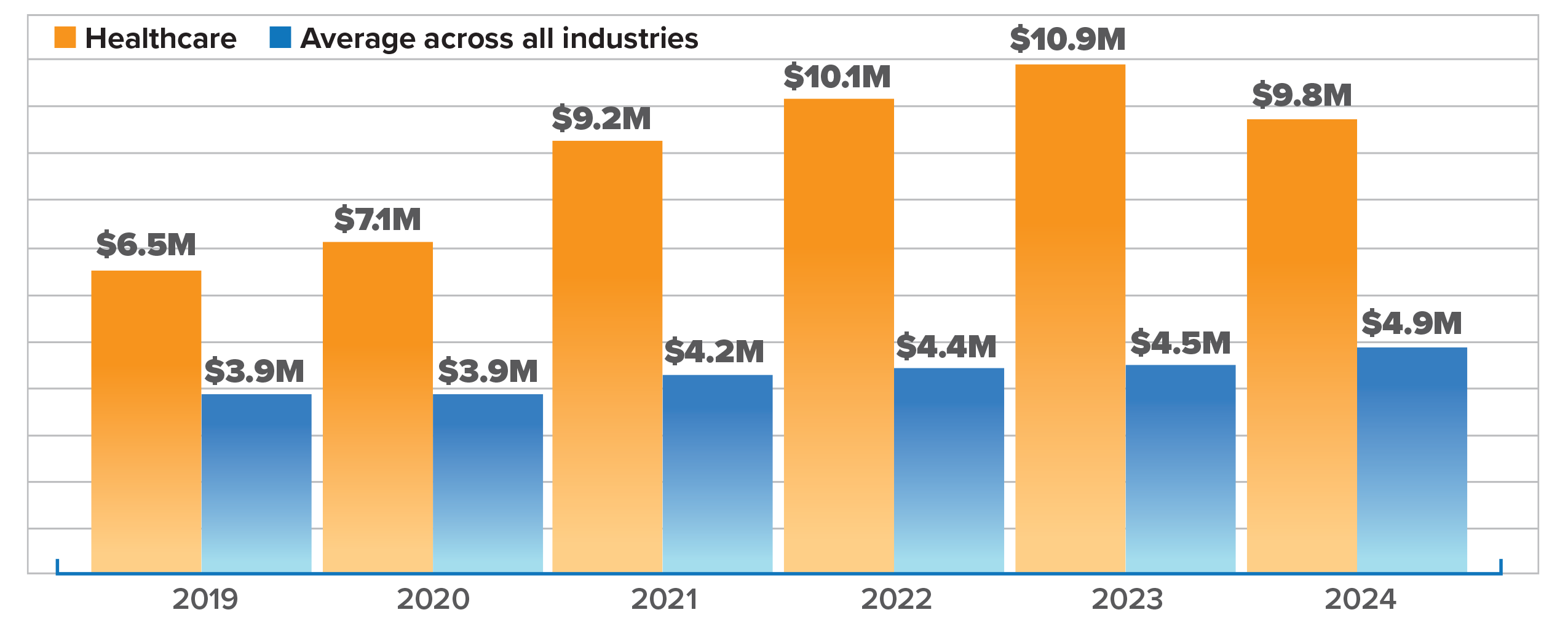

James Hereford, president and CEO of Fairview Health Services, is at the helm of one of the organizations significantly affected by the Change Healthcare incident. The Minneapolis-based health system reportedly lost more than $7 million due to the attack, causing consequential financial harm.

Hereford recalls when his mindset on cybersecurity centered on prevention: “I just thought about it in terms of we have to harden the shell so it’s harder to get into. And yes, you have to do that… but it has to go beyond that.”

SOURCE: Kanini

Part of that “beyond” is recognizing that people, from executives to frontline staff, can be the weak link. “We’re our own worst enemy,” Hereford says. “It’s how do we keep people, all of us, vigilant about ‘don’t click on that link.’”

Fairview Health Services lost more than $7 million due to the Change Healthcare cyberattack in February 2024.

Source: Fairview Health Services leadership, reported post-incident

Fairview still does preventative work, but with a clear-eyed realization that bad actors are likely to breach its systems. “How do you isolate what they have access to? Can we recover quickly and can we prioritize the recovery around what are the things that we need to do to be able to continue to deliver patient care,” Hereford says. The organization has invested in hot sites, failover sites, and alternative workflows when systems like the electronic health record are down, he notes.

The shift from thinking about cybersecurity as purely an IT problem to viewing it as a clinical continuity problem is increasingly common. Recovery drills, backup systems, and scenario planning have become part of organizations’ day-to-day operations.

Legal, Financial, and Survival Stakes

For hospitals and health systems, the protection that cybersecurity provides safeguards more than just financial interests.

Cyber events are foreseeable, which means they carry legal weight, according to Mike Hamilton, field chief information security officer at Lumifi Cybersecurity and former CISO for the City of Seattle. “If you fail to take steps to mitigate a foreseeable risk, you’re guilty of negligence,” he states.

The growing sophistication of attackers means hospitals can’t expect to win every battle. “Hospitals cannot go glove to glove with these people and win,” Hamilton says.

Saad Chaudhry

chief digital and information officer at SSM Health

To protect themselves, hospitals should invest in immutable backups and an incident response retainer through an insurance company or through a third-party provider. Done right, that preparation can insulate an organization from worst-case scenarios like class action lawsuits, Hamilton highlights.

Privacy laws complicate the picture. “Our hospitals are taking these huge financial hits,” Hamilton says. “If we had a national privacy statute that supersedes the state’s private right of action, we would lose fewer hospitals. Some of these guys close after a cyberattack.”

“An average health system of 10,000 users is being attacked an average of 200 times per second. In this monologue that I just gave you, we’ve all been attacked tens of thousands of times already.”

—Saad Chaudhry, chief digital and information officer, SSM Health

Hospitals are already under financial strain from labor costs, inflation, and declining reimbursement. A major cyber event, combined with litigation, can push them to insolvency. That’s why Hamilton frames resilience not just as a technical issue, but as survival economics.

For small and rural hospitals, the stakes are even higher. “That hospital may have an IT department of five people or less sometimes,” Chaudhry says. “So imagine what happens when an incident happens here. The communities that count on that hospital now cannot get the care as rapidly as they need.”

The danger isn’t theoretical. In practice, one successful phishing email can paralyze a hospital and force ambulances to divert. For rural communities, it could mean hours-long delays in care. “That could be the difference between life and death,” Chaudhry says.

Outsourcing help often costs more than insourcing, he notes, yet rural facilities often lack the cash for either. “Rural America needing resources to respond to attacks rapidly is absolutely a critical investment factor for the United States,” Chaudhry says.

Hamilton worries that without intervention, “the big companies are going to come in and scoop up rural hospitals for pennies on the dollar” after attacks push them to the brink.

James Hereford

president and CEO of Fairview Health Services

Policy Gaps and Regulatory Solutions

Both Chaudhry and Hamilton believe policy changes are key, with alignment of resources needed at the state and federal level of government.

Chaudhry envisions a government-sponsored cybersecurity response network with rapid response built in, “no different than when our phones lose signal and you can still call 911.” Certification could ensure only truly resource-limited hospitals qualify.

He cautions against policies that are too broad or too complex. “If you just make it too broad, then the people that actually need the help may not get all the help they want because the funds and network will be separated out. If you make it too hard, then the people that actually need it may not actually get it.”

Hamilton advocates for a national privacy statute to prevent costly lawsuits after breaches and a targeted grant program to support rural healthcare. “We need a grant program specifically to reach out to rural health. Being able to mitigate to blunt the loss of Medicaid money with a grant program is a really good idea.”

He also points to the role of states in filling gaps left by federal agencies. For example, the Cybersecurity Information Sharing Act (CISA) of 2015 is set to expire at the end of September unless Congress acts. The law has allowed for the rapid sharing of threat intelligence between the federal government and private sector.

Ransomware incidents on healthcare delivery organizations more than doubled between 2016 and 2021.

Source: JAMA Health Forum

“If information sharing degrades after CISA 2015’s sunset, hospitals–and all other critical infrastructure–very likely will lose crucial early warnings about ransomware variants and other attack methods,” Cynthia Kaiser, former deputy director of the FBI’s cyber unit, wrote in Fortune. “When a hospital’s systems are threatened, rapid information sharing matters.”

Hamilton believes states should aim to recreate the information sharing that will be lost if CISA expires.

“One big thing that states really need to get in front of here is statewide monitoring,” Hamilton says. “So the state will have a [security operations center] and do that for the benefit of everybody else.”

SOURCE: HIPAA Journal

Tech Isn’t Enough: Culture and Governance Matter

Even with policy help, hospitals and health systems must still protect against emerging technologies that are raising the bar for defense.

“There will come a time where it’ll become very, very hard to detect what is real and what is AI generated,” Chaudhry says.

Attackers could weaponize AI for timing and targeting. “In your moments of vulnerability, you will be threatened even more. That is the AI guarantee in the information security world,” he says.

“Hospitals cannot go glove to glove with [hackers] and win.”

—Mike Hamilton, field Chief information security officer, Lumifi Cybersecurity; Former CISO, City of Seattle

Mike Hamilton

field chief information security officer at Lumifi Cybersecurity and former CISO for the City of Seattle

Hamilton describes an “arms race” where vendors are baking AI into defensive tools, from Microsoft’s Sentinel to specialized network detection platforms, to filter out false alerts and catch real threats faster. “As long as the vendors keep making investments and making their stuff better, it’s pretty much going to be robot to robot,” he says.

AI also poses a cultural challenge. Traditional training methods, like teaching employees to spot misspellings in phishing emails, are less useful when AI can generate flawless, convincing messages. That forces organizations to emphasize layered defenses and rapid detection instead of relying on human vigilance alone.

The human touch shouldn’t be overlooked though. Having the right leaders in place is essential, according to Hereford, who describes Fairview’s structure where the CIO, CISO, COO, CFO, and legal/risk leaders work in lockstep on recovery priorities. Board-level involvement adds another layer.

“That alignment from really board-level governance all the way through the leadership team and through the leaders is critical in my mind,” Hereford says.

Hamilton, meanwhile, stresses risk governance. He points to the NIST Cybersecurity Framework, which emphasizes the responsibility of risk management at the executive level of organizations.

Chaudhry urges executives to run regular tabletop exercises. “If you can just get to a place where you can figure out communications and who to turn to, you’re already further ahead than most,” he says.

For hospitals, resilience requires the ongoing fostering and maintenance of culture. Training, communication, and accountability ensure that when an incident occurs, the response is coordinated rather than chaotic.

In 2024, healthcare faced more cyberthreats than any other critical infrastructure, with 238 ransomware threats and 206 data breaches.

Source: FBI Internet Crime Report

SOURCE: IBM

A Collective Problem

Ultimately, experts agree that hospitals, especially small and rural ones, can’t tackle the cybersecurity problem alone. Chaudhry likens the needed shift to the evolution of automobile safety with seatbelts, airbags, and accident response.

“We need a standard, regulated way of responding… because they absolutely 100% will happen,” he says.

Until there is more regulation and standardization, hospitals will continue facing what Hamilton calls “robot to robot” battles in cyberspace, where resilience is measured by survival.

For now, health system leaders like Hereford are caught in a difficult balance of investing in cybersecurity while also competing with demands for “big buildings, big equipment, expensive people.” As he puts it, “I always feel like I can never spend enough money… but I know it’s imperfect and we continue to try to get a little bit better every day, just as the bad guys get a little bit better and more sophisticated all the time.”

What’s clear is that the future of hospital cybersecurity will be all about preparedness: accepting that attacks are inevitable and building resilience into operations to ensure that patients, regardless of where they live, can keep receiving care.

Jay Asser, CEO Editor, HealthLeaders

Subscribe to HealthLeaders CEO Newsletter + Daily Briefing

By subscribing to HealthLeaders I agree to sign up to receive newsletters and special offers. I understand that I can opt out at any time. Privacy policy.