COVER STORY

August 2025

TCFOs Have the Financial Data. The Numbers Aren’t on This Care Model’s Side.

Hospital-at-Home (HaH) promised to revolutionize healthcare delivery, freeing up beds, cutting costs, and keeping patients happier at home. But CFOs face a stark truth: without bold cost restructuring and strategic scale, the model’s financial foundation may crumble before it ever delivers on its promise.

COVER STORY

August 2025

CFOs Have the Financial Data. The Numbers Aren’t on This Care Model’s Side.

Hospital-at-Home (HaH) promised to revolutionize healthcare delivery, freeing up beds, cutting costs, and keeping patients happier at home. But CFOs face a stark truth: without bold cost restructuring and strategic scale, the model’s financial foundation may crumble before it ever delivers on its promise.

TAKEAWAYS

- While HaH shows strong patient satisfaction, fewer readmissions, and better outcomes, most programs struggle to produce sustainable profit margins.

-

Traditional hospital overhead models distort ROI. CFOs must design ground-up financial frameworks that isolate true HaH costs.

- Programs serving fewer than 30–60 patients per day often cannot reach the cost efficiencies needed to compete with inpatient care.

- HaH success requires patience, leadership alignment, and a shift in financial expectations.

TAKEAWAYS

- While HaH shows strong patient satisfaction, fewer readmissions, and better outcomes, most programs struggle to produce sustainable profit margins.

-

Traditional hospital overhead models distort ROI. CFOs must design ground-up financial frameworks that isolate true HaH costs.

-

Programs serving fewer than 30–60 patients per day often cannot reach the cost efficiencies needed to compete with inpatient care.

-

HaH success requires patience, leadership alignment, and a shift in financial expectations.

It was billed as the future of acute care delivery—a model that could free up beds, cut costs, and delight patients. Yet for all its clinical wins, the financial upside of Hospital-at-Home (HaH) is far murkier than the headlines suggest. For most health systems, the strategy is more about capacity relief than cash flow.

The ROI isn’t in the black ink, it’s in fewer readmissions, happier patients, and the elusive promise of long-term sustainability.

More than 400 hospitals have launched CMS-defined Acute Hospital Care at Home programs, riding a wave of pandemic-era necessity and a CMS waiver that unlocked Medicare reimbursement.

But with regulatory uncertainty, CFOs are staring down a blunt question: if the reimbursement goes away—or even shifts—does this model still make sense?

The truth is, HaH can work financially, but only if leaders rethink cost structures from the ground up, abandon traditional hospital accounting assumptions, and scale with precision.

The unspoken reality: Without deliberate financial design, most programs will sputter out, undone not by clinical failure, but by cost curves that never bend in their favor.

For CFOs, the challenge isn’t just proving HaH can save money; it’s ensuring the model can survive long enough to deliver the real return: a future where high-acuity care is no longer bound by hospital walls.

Hospital-at-Home Is In a Cost Crisis

The uncomfortable truth? Hospital-at-Home fails under the weight of conventional cost modeling. Lump in fixed hospital overhead, and you’ve doomed your ROI before the first home visit.

To survive, CFOs must dismantle their unit economics and rebuild from the ground up, shedding outdated assumptions and making every dollar serve the model’s unique realities.

There’s a need for detailed financial analysis up front, and many HaH programs go under due to inadequate financial modeling. Traditional cost modeling just doesn’t translate, says Tom Kiesau, the chief innovation officer and leader of digital & technology transformation at Chartis.

Kiesau says understanding the whole financial picture starts with redefining unit-based cost analysis and separating hospital-based overhead from the actual costs of delivering care in the home.

“If you don't break apart your capital and your overhead allocations and build them up from ground zero, you are going to burden your hospital at home infrastructure with unrealistic and inaccurate costs,” Kiesau warns.

Fixed costs like food services, security, or cleaning staff don’t belong in the HaH model, he says, and including them will skew your ROI calculations. Instead, CFOs must build a ground-up business case that includes per-encounter variable costs, right-sized capital investments, and deliberate sequencing of resource deployment.

“You can't lose money on the margin and make it up on volume,” Kiesau says.

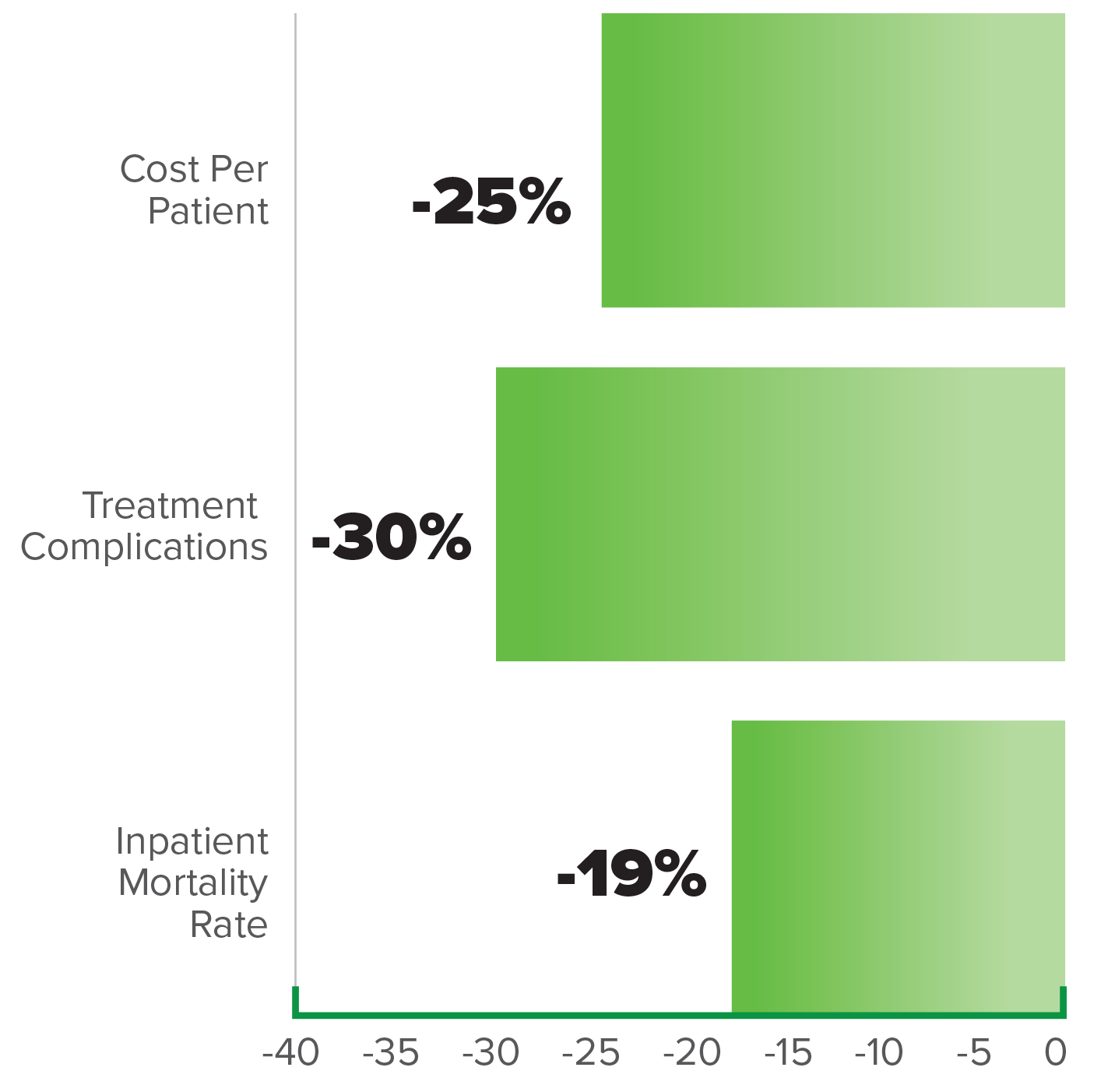

Growth of Hospital-at-Home (HaH) Model and Outcomes

SOURCE: Growth of Hospital-at-Home (HaH) Model and Outcomes

While Kiesau says that most programs fail to mature because they don’t start with clear financial modeling or track their capital release strategy, one CFO has a different perspective.

Tom Kiesau

chief innovation officer and leader of digital & technology transformation at Chartis

Mass General Brigham (MGB) has emerged as a national leader in HaH, both in patient volume and financial strategy. According to MGB’s CFO and Treasurer Niyum Gandhi, the business case for HaH evolved not by focusing strictly on profitability, but on long-term sustainability and care quality.

“Our job is not to optimize finances. Our job is to deliver the highest quality care possible in a financially sustainable manner,” he says.

Initially, the costs of delivering care at home were higher due to labor inefficiencies like travel time. But MGB recognized a tipping point.

“At a certain scale point you reach economics such that the underlying cost to deliver the service is less expensive than if you're doing it in the hospital,” he says.

That scale, he explained, comes around the “mid double digits”— roughly 60 to 70 patients per day.

Interestingly, he discourages traditional break-even analyses.

“I refrain from asking [my team] to do the break-even analysis... because it's going to take you hours and hours and hours to do that and the variations in the census numbers – whether they are 30 or 40 or 50 – do not significantly impact our decisions,” he says.

Instead, the focus is on whether the program can operate without major losses, while maintaining or improving care outcomes. And the outcomes are compelling: lower mortality, fewer readmissions, and higher patient satisfaction.

“The ROI on it, it's better outcomes,” he says.

Rather than aiming for highly detailed or “perfect” cost accounting, MGB’s finance team focuses on capturing the key direct costs, such as nurse visits, physician visits, and remote patient monitoring (RPM), at a level that is sufficient to guide strategic decisions, like whether or not to expand the program. Gandhi dismisses over-engineered cost models, especially for new care delivery models, arguing that exhaustive analytics often fail to influence actual decisions.

“I could absolutely deploy an A-Team to go spend three months doing perfect cost accounting for Home Hospital, and with that information we would make no different decisions,” he says. “So, it would actually be a bad use of resources to do that cost accounting.”

This mindset reflects a broader concern that the healthcare industry often over-prioritizes data precision at the expense of practical value. Instead, Gandhi advocates for a “good enough” analysis that balances resource use with insight generation.

“I think at a certain point you do need to start drilling into trying to improve the unity economics of everything, because the better the unit economics of any given service, the more of that service we can provide in a cost-effective way,” Gandhi says. “But I think we get so caught up on wanting to do very detailed financial analysis that we lose track of thinking in the long-term. No advancement in care delivery was ever perfect financially in the first year. It takes time.”

“The trough of building a hospital-at-home to scale versus building a hospital, it’s staggering. The ROI curve is just so much bigger.”

—Tom Kiesau, chief innovation officer and leader of digital & technology transformation at Chartis

The goal is to understand whether the program is financially viable and scalable—not to account for every penny spent. With clinical value leading the way, the financial case for HaH becomes clear, not as a cost-cutter, but as a scalable, sustainable model for delivering high-quality care outside the hospital walls.

Additionally, CFOs will need to consider how new infrastructure, such as logistics hubs or supply chain systems, can be allocated and whether to build or outsource. As capabilities grow to include observation-at-home or post-acute care, the program’s capital assets are leveraged across multiple revenue models, driving unit costs down and improving margins.

Kiesau encourages CFOs to embrace a phased approach: “Know your volumes. Don’t go all in at once. Track it and monitor it.”

“The competition isn’t the other hospitals. The competition is death and disease.”

—Niyum Gandhi, CFO and Treasurer of Mass General Brigham

While HaH isn’t a silver bullet, its value can’t be understated.

“The trough of building a hospital-at-home to scale versus building a hospital, it’s staggering,” Kiesau says. “The ROI curve is just so much bigger.”

UNC Health dove into the HaH space in 2021 when the system partnered with Medically Home to launch its Acute Care at Home Program. UNC Health’s CFO, William Bryant, explains how waivers and increased payer support for virtual care during COVID-19 made the HaH model financially viable.

"The pandemic was really the impetus for the program," says Bryant.

Initially expected to break even at 15 patients per day, early results revealed that labor costs were higher than anticipated and payer support was more limited, which prompted a shift from external to internal staffing.

"For us it always has been a capacity generation and an access play more than a direct financial benefit," Bryant emphasized, noting that the program primarily helps alleviate overcrowded facilities.

Despite mixed payer engagement, strong patient satisfaction and encouraging quality metrics have supported continued investment in the model.

HaH Lessons From Veteran CFOs

The act of balancing capital allocation between brick‑and‑mortar expansions against investments needed for HaH, such as RPM tech, supply‑chain platforms, and care coordination systems, can get complicated, especially during periods when inpatient revenue is under pressure.

At MGB, Gandhi says they view investment in HaH as higher yield than capital expenditures on brick-and-mortar expansions because running the HaH program is more capital-efficient long-term.

“We, of course, continue to have to make investments in brick-and-mortar inpatient capacity, given the persistent capacity crisis in Massachusetts (despite the scaling of our Home Hospital) and given that we have a lot of capacity that is due for replacement,” says Gandhi. “But none of that cannibalizes our necessary investments in Home Hospital.”

Niyum Gandhi

CFO and Treasurer of Mass General Brigham

Gandhi explains that while HaH has higher labor demands, technology offsets costs, making it “plus or minus 5–10%” compared to inpatient care. Virtual care reduces some staffing needs, while home visits increase others, resulting in a financial balance. The key advantage is long-term flexibility and avoiding infrastructure costs.

“That’s pretty material in terms of savings of actual real brick-and-mortar cost,” Gandhi says.

“Our job is not to optimize finances. Our job is to deliver the highest quality care possible in a financially sustainable manner.”

—Niyum Gandhi, CFO and Treasurer of Mass General Brigham

HaH allows health systems to scale capacity seasonally or in response to demand without investing in costly, time-consuming capital projects, helping maintain financial efficiency and responsiveness.

To ensure sustainable investment in HaH programs, CFOs should integrate HaH into broader capital planning, accounting for scalable infrastructure and potential impaired assets. HaH can be rapidly deployed to manage surges without the cost or time of new construction, making it a strategic “relief valve” for capacity.

HaH typically lowers per-discharge costs and can reduce operating expenses without major staffing increases. However, CFOs must assess potential cannibalization of inpatient revenue and model financial impacts carefully.

A key pitfall is misattributing revenue. Kiesau draws a comparison: if a patient moves from the ICU to med-surg, the revenue shifts accordingly. The same logic must apply to HaH. HaH revenue must be tracked like any inpatient transition—comparable to moving a patient from ICU to med-surg. Over or underestimating HaH revenue undermines accurate financial planning.

Scrutinizing early capital investments and projecting patient volumes with population health data are essential to avoid overinvestment and underperformance.

Kiesau says HaH doesn’t necessarily require large upfront investments; in fact, its scalability is one of its greatest financial advantages.

“You can get the core element of your model in place, and you can add capabilities in the next tranche,” he says.

Technology’s Role in Financial Success and Scalability

While financial modeling remains critical, Kiesau notes that the real value of technology in HaH lies in optimizing operations and reducing risk, not just refining budget projections.

“Machine learning models are actually good at finding these relationships and estimating utilization patterns prospectively,” he says.

“For us it always has been a capacity generation and an access play more than a direct financial benefit.”

—William Bryant, CFO of UNC Health

Predictive analytics can help identify which patients are best suited for HaH and, more importantly, flag early signs of deterioration before they lead to rehospitalizations.

Health systems don’t get to skip safety protocols, but they can apply existing academic models in AI and machine learning to improve patient selection and monitoring. These technologies support more confident scaling of HaH programs while protecting both clinical quality and cost predictability.

AI also plays a growing role in logistics. From determining which medical devices are needed for each patient, to tracking device usage and performance, automation supports smarter, leaner HaH operations.

“AI is monitoring the signal at all times and pushing it up to the care teams,” Kiesau explains.

And perhaps most notably, HaH may soon drive tech-forward thinking across the entire hospital.

“Hospital-at-home will become the innovation engine,” Kiesau says. “We’ll look at the hospital and say, ‘Why are we doing this manually in the hospital? We’ve got all these signals with monitoring algorithms and process automation that are working in the home.’”

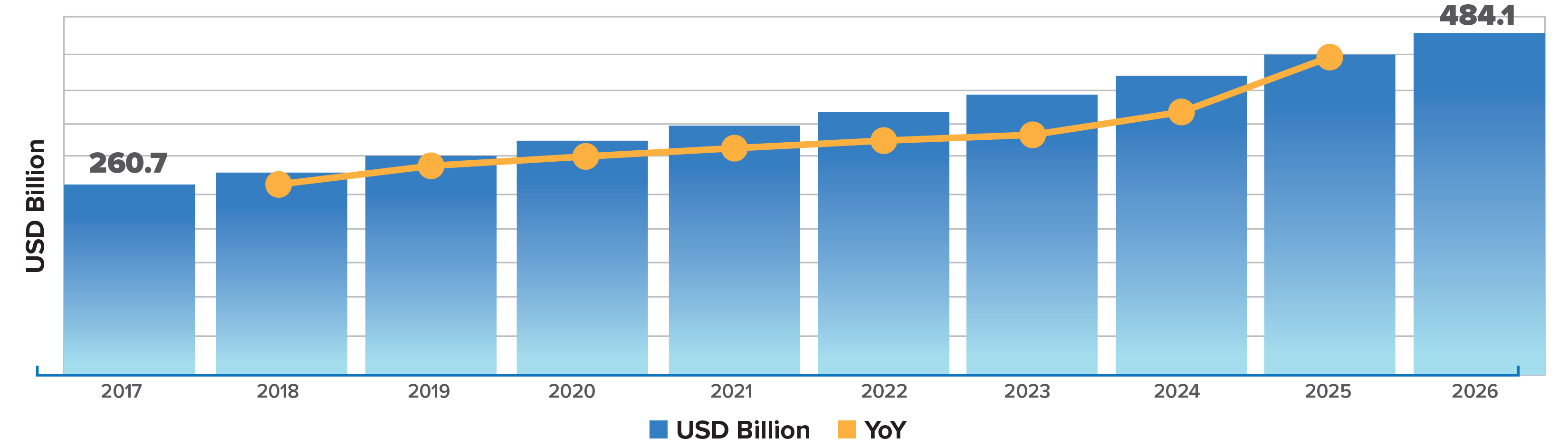

Home Healthcare Market (USD Billion) & YoY Growth (%)

SOURCE: Home Healthcare Market (USD Billion) & YoY Growth (%).

For CFOs, investing in HaH infrastructure isn’t just a cost-containment strategy, it’s a forward-looking play that could modernize broader clinical operations over time.

For HaH programs to succeed financially, health systems must rethink their IT and data infrastructure. Kiesau emphasizes that true visibility into cost and performance will ultimately require integration across the "big three" systems of record: the EHR, enterprise resource planning (ERP), and customer relationship management (CRM) platforms.

“These systems have traditionally not been well integrated,” Kiesau says. “But to understand the cost of interacting with patients—and to tell the full story of care—we need to link them in entirely new ways.”

“You can't lose money on the margin and make it up on volume.”

—Tom Kiesau, chief innovation officer and leader of digital & technology transformation at Chartis

This integration is critical not only for real-time clinical decision-making, but also for long-term cost tracking as the lines between care settings blur. CFOs should pay close attention to the logistics layer of IT infrastructure: the cost of deploying, monitoring, and retrieving remote devices, and how those costs align with reimbursement.

Seemingly minor operational details, like tracking and monitoring RPM devices, for example, can significantly impact ROI.

“These are the kind of details that will cumulatively make or break a health system’s HaH infrastructure scalability,” Kiesau says.

By aligning IT systems and cost data, CFOs can unlock new capabilities that drive smarter investments and long-term program sustainability.

Finance-driven dashboards to track resource utilization and profitability by geography, episode type, and patient cohort also play an important role. On top of leveraging existing standard inpatient reporting for HaH, MGB’s analytics team has also built what Gandhi calls a “very helpful” set of dashboards to specifically track quality, operating performance, and the financial sustainability of its HaH program.

UNC Health’s HaH model also utilizes in-house analytics that aid in the operational overview.

“We have a very strong data analytics function within our organization. So, we have the ability to develop our own internal dashboards, which update daily from an operational standpoint,” Bryant says.

Clinicians Can Make or Break Your Model

CFOs can engineer the perfect financial plan, but without clinician buy-in, the model flatlines. Early enthusiasm is fragile, and operational missteps can erode trust fast. Retaining clinical champions and building flexible, scalable staffing models is as critical to survival as any line item in the budget.

Case in point: UNC Health. Clinician support for UNC’s HaH program was developed group by group, with some physicians eager to participate from the start.

“We had a number of physicians that stepped forward, raised their hands and said, ‘I’d like to be part of this,’” Bryant noted.

They praised the model’s flexibility in allowing both full-time and part-time clinical involvement. While some traditional hospital operators initially had concerns about safety and logistics, Bryant says staff got on board from a clinical standpoint surprisingly fast once positive results emerged.

However, getting all frontline providers, especially ED physicians, to consistently consider HaH as a first option remains a challenge. Limited early capacity created missed referral opportunities, which Bryant acknowledged may have discouraged some clinicians. Now, with expanded capacity, the organization is planning renewed outreach and education to re-engage providers and build momentum for broader clinical adoption.

“No advancement in care delivery was ever perfect financially in the first year. It takes time.”

—Niyum Gandhi, CFO and Treasurer of Mass General Brigham

An HaH program isn’t just a clinical care model, it’s a strategic workforce tool. Kiesau frames HaH as a clinician retention and recruitment strategy, offering more flexible roles in home settings or command centers.

“As programs get bigger, the primary recruitment source is often people opting out of other health system jobs to go into this job,” he notes.

The CFO Playbook: Survive Now, Profit Later

HaH discussions are often dominated by clinical voices, but CFO engagement is essential for scalable, profitable growth.

“Because it’s a new care setting, whenever I present on HaH, the audience is always clinicians—there are zero financial executives in the room,” Kiesau says.

A key lesson in UNC Health’s HaH program was the importance of building a “scalable and quickly scalable” model, because smaller programs with only 10–15 patients per day aren't sustainable long-term. Bryant emphasized setting a clear path to reach at least 30 patients daily to maintain momentum and internal support. Strong executive and physician backing was also critical to success, as misalignment within leadership or clinical teams can stall the program’s progress.

“I can't imagine trying to implement a model like this without having strong physician support,” he says.

“I can't imagine trying to implement a model like this without having strong physician support.”

—William Bryant: CFO of UNC Health

While many health systems launch their own HaH programs internally, others contract with vendors to handle technology and even daily monitoring and in-person visits. For his part, Bryant recommends using external partners to launch the program but be ready to pivot when that partnership no longer adds value. He also urges CFOs to get straight with payers from the start.

"Get your payer relationships lined up on the front end," Bryant advises, noting that early assumptions about payer alignment didn’t pan out, which created financial and operational challenges.

Lastly, Bryant says, don’t treat it like a pilot.

“I think one of the mistakes that we made when we implemented it early on was we treated it like a pilot and kind of continued to treat it like a pilot,” he says. “I really do think you have to scale these programs from the start and almost over invest in your resources to be able to absorb the capacity, because what we're finding now is that our capacity is constrained.”

Gandhi advises new HaH adopters to take the long view, avoid overengineering, and ensure strong leadership support. Financial sustainability shouldn’t be judged too early.

“Give it a time frame,” he says. “Treat it like a real commitment.”

Define clear clinical and financial outcomes and measure performance rigorously. Focus on delivering better patient outcomes, not just breaking even. Finally, leverage the collaborative spirit in healthcare: reach out to other systems for shared learnings.

“The competition isn’t the other hospitals,” Gandhi says. “The competition is death and disease.”

The Financial Future of HaH

The countdown is on. If the CMS waiver disappears later this year, so does the clearest path to reimbursement for most HaH programs. Without it, patient volumes could collapse, margins could vanish, and CFOs will be forced to choose between propping up a program with shaky returns or pulling the plug entirely.

“It's one of the most broadly adopted waivers in history,” says Kiesau. “It is now in the popular press. It's not even just healthcare press. It's in the Wall Street Journal.”

William Bryant

CFO of UNC Health

Some healthcare executives believe HaH programs are here to stay, regardless of the Medicare waiver decision, but there will be noticeable differences and bigger risk for some systems.

Gandhi emphasized that without the CMS waiver that is set to expire, the financial sustainability of HaH programs is at risk, especially for smaller health systems.

"If CMS stops paying for it, I think what we'll realize is a lot of scale programs will become subscale,” he says.

Medicare patients make up a large share of eligible admissions, so losing traditional Medicare coverage would significantly shrink patient volumes. Programs would then face higher administrative burdens and payer eligibility checks, straining operations and frustrating clinicians. Gandhi also highlights difficulties in negotiating with payers when care decisions are dictated by insurance rather than clinical appropriateness.

“We're hopeful that CMS has seen, as we certainly have seen, the value of this program both in terms of its ability to get great outcomes and have exceptional patient experience,” adds Bryant. “With this population compared to the overall population, we’ve seen lower readmission rates and higher patient satisfaction.”

Hospital-at-Home is not a short-term cost cutter. It’s a long-term capacity and care transformation play. The winners will be the CFOs who resist overengineering, scale deliberately, and make bold, sustained investments in infrastructure, workforce, and payer alignment.

In a market where beds are finite and capital is tight, this is the pivot that will decide who thrives.

Marie DeFreitas, CFO Editor, HealthLeaders

Subscribe to HealthLeaders CFO Newsletter + Daily Briefing

By subscribing to HealthLeaders I agree to sign up to receive newsletters and special offers. I understand that I can opt out at any time. Privacy policy.